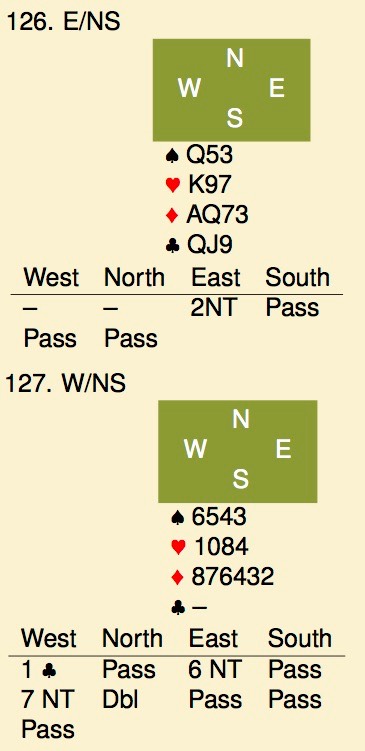

In the previous episode of this blog, I reported on the first, unofficial, world championship played in 1933. While the 1933 event was billed as a world championship, it certainly wasn’t the first match between teams from different countries. One such match was played some 3 years before, when a British and American team met for a 200 board match. Of course, nobody knows if this was the first interland in history. It is, however, the first international match that was properly recorded and published in a book. As a start, here are a few hands where you find yourself on lead. On board 126, 2NT is a strong balanced 20-22 count, on 127 all the bids are natural, east thinking he can make 6NT, west thinking he can do a trick better.

It is, however, the first international match that was properly recorded and published in a book. As a start, here are a few hands where you find yourself on lead. On board 126, 2NT is a strong balanced 20-22 count, on 127 all the bids are natural, east thinking he can make 6NT, west thinking he can do a trick better.

Note: there is an error in the diagram, on board 126, the heart suit should be J97, not K97.

Some background on the match. Contract bridge was introduced in the late 1920’s in the US after Harold Vanderbilt published his rules. Contract Bridge wasn’t an entirely new game, card games where fixed partnerships take tricks had been around before. Examples are Whist, Dummy Whist and Auction bridge. Contract bridge added 2 new elements: first the concept of “game” where only bonusses were awarded for tricks bid and made, secondly the concept of “vulnerability” with its effects on the score. Those changes made Contract Bridge a far more attractive game than Whist or Auction Bridge, and it quickly replaced the two.

While the game of contract bridge originated in the USA, the game quickly made it across the Atlantic to the British (gentleman) clubs. One of the players who introduced the game in the UK, was Lieutanant-Colonel Walter Buller, a retired army officer who spent his time playing whist and auction bridge but was one of the first to switch.

Of course, with the Culbertson organization trying to promote the game in the US, and the British with their history of playing whist and similar games, the question quickly arose where the strongest game was played. Buller has been attributed to write that “the suggestion that the Americans are vastly superior to us at bridge, is a fantasy”. That is something one shouldn’t say to Culbertson.

The upshot was that a match was held between September 15 and 21, 1933, with two teams: On the Britsh side that was Walter Buller (captain) playing with Alice Evers, and Nelson Wood-Hill and Cedric Kehoe. The American fielded Ely and Josephine Culbertson and Theodore Lightner - Waldemar von Zedwitz, though these 4 played in other line-ups as well. It is a sign of the times that all players are referred to as Mr. or Mrs., or Dr. Wood-Hill and Lt.Col.

The match was a 200 board event, played as a team-of-four match pretty much as we know today. The event took 6 days and was held at Almack’s club in London, a social club that had been around since 1765 as a place for the British aristocrats to socialize. A few other differences: in those days, all tricks bid in NT scored 35 points, rather than today’s 40 for the first and then 30 for any other tricks. Undoubled overtricks were always worth 50 points. So, 3NT, not vulnerable, making an overtrick, was worth 455 points (3x35, plus 300, plus 50). Dealer and vulnerability followed a somewhat different pattern from today. Finally, the event was scored as total points, that is, simply add up the scores from each pair of a team in both rooms. The team with a positive balance wins. Play was recorded by officials and published in a book. The hands are presented as both bid and play records, without any comments, though there is a 10 page introduction by the British captain. More about that later, time for a couple of hands.

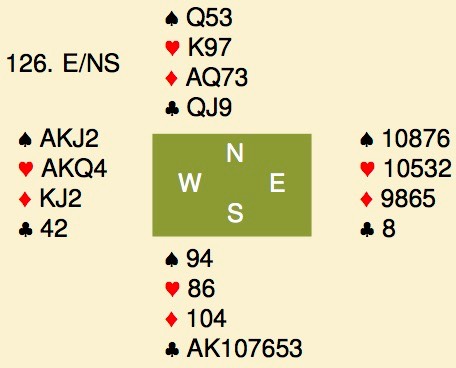

The British west opened a strong 2NT and this was passed around.

Note: there are 2 ♥K in the diagram (and no ♥J). North has the ♥J, not the K. This doesn’t affect the discussion.

I’d think that a ♣-lead is fairly standard, you don’t want to lead away from ♦AQxx and the other suits promise a lot less in terms of developping tricks. So, north led the ♣Q, all small and continued the suit. That set up the first 7 tricks for the defence. On the clubs, declarer discarded the ♦2 from his hand and the ♦65 from the dummy, so that set up another 4 tricks. Down 6, or -300, which looks a bit silly but is a normal result. In the replay, EW bid 4♥ played by west. On a ♦10 lead, that was down from the start as well.

Why am I showing this hand? One of the things bridge players are known to do, is to complain about the opponent’s actions, in particular when they turn out well. Here the book reads “an American innovation [unknown to us] was to lead a short suit against NT”, and “when a ♣2 was led against NT, I could not put the leader with a 4 card suit”. Wow, not leading the 4th best from your longest and strongest, that must have been a shock. The book goes on for a paragraph or two complaining that the loss of 200 points was completely unlucky. It doesn’t say anything about the next hand though.

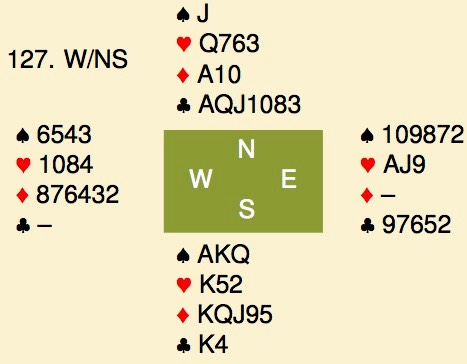

Ace asking had not been invented, the British north had some extra’s for his 1♣ opener, so he raised. East looked at the setting trick, all his partner had to do is to find the right lead.

In practice, he led a diamond and declarer quickly claimed 13 tricks. The only argument I can see, is that hearts are the shortest suit making it a little more likely that partner’s values are there, but it is a very weak argument and the lead is pretty much a toss-up. That added up to 1840 points to NS, and a gain of 820 over the 6♣ at the other table. Holding ♣AQJ10 of trumps gave you a 100 point bonus back in those days. If somebody would have reason to complain about bad luck, I think the Americans have a far better reason for this.

Incidentally, the west player on lead was Theodore Lightner, who would later become famous for the double against slams.

Obviously, there is a lot more material to write about, so to be continued in a next episode.